Bringing SQL to MongoDB with Apache Drill

If you’re reading this post, then chances are you’ve found yourself wishing you could talk to your MongoDB data store using a standard SQL interface. There are lots of good reasons to do this: Maybe you’d like to port some existing code with a minimum of fuss, or maybe you’re dealing with a lot of different data storage types and would like to unify them all under a single interface (hint: Apache Drill is fantastic for this). Whatever your reason, this guide will step you through a simple single-computer example of how to connect these two tools. I’ll be demonstrating how to accomplish this task on a Linux system, but MongoDB and Apache Drill are both available for OS X and Windows as well.

Step 1: Install MongoDB

First we need to download a tarball of the MongoDB software, so pop open a terminal and grab it with this command:

$ wget https://fastdl.mongodb.org/linux/mongodb-linux-x86_64-3.0.6.tgz

Next we’ll make a folder in our home directory where MongoDB will reside, extract the tarball we downloaded, and copy the contents to that directory (feel free to delete redundant files as you go here):

$ mkdir ~/mongodb

$ tar xzvf mongodb-linux-x86_64–3.0.6.tgz

$ cp -r ~/mongodb-linux-x86_64–3.0.6/* ~/mongodb

It would probably be a good idea to put the MongoDB binaries directory in the system PATH, so edit ~/.bashrc and insert this statement:

export PATH=~/mongodb/bin:$PATH

Now we’ll make a folder to house MongoDB databases within our home directory, and start the MongoDB daemon.

$ mkdir ~/mongodb/data

$ mongod --dbpath ~/mongodb/data &

Or if you’d prefer to not have the daemon attached to your terminal (so it can stay open when you close the window) instead run:

$ nohup mongod --dbpath ~/mongodb/data &

Step 2: Loading Some Example Data Into MongoDB

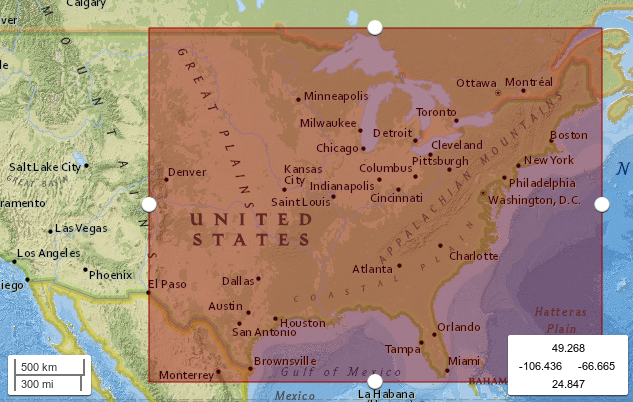

For the example data in this guide I’ve decided to use the results of a query to this USGS archive of seismic events. I ended up taking all events from 1980 through 2014 that occurred within a region that I defined using the web interface (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: My example data set contains seismic event data from this region of the United States. Events date from Jan. 1, 1980 to Dec. 31, 2014.

A number of options are available for output on the web site, and I decided to go with CSV. We can import a CSV file (in this case the result of the USGS query, renamed to ‘quakes.csv’) into MongoDB using the following command:

$ mongoimport --db quakedata --type csv --headerline --file quakes.csv

Note: This command creates a MongoDB collection called ‘quakes’ in a database named ‘quakedata.’ To verify that the imported data is indeed accessible via our MongoDB server, we enter the mongo shell by typing

$ mongo

Now we can switch to the ‘quakedata’ database, and enter this simple query which asks for a single event with a magnitude of 5.1:

> use quakedata

switched to db quakedata

> db.quakes.find({mag:5.1}).limit(1).pretty()

{

"_id" : ObjectId("55fdd74548f529cf40132523"),

"time" : "1983–10–07T10:18:46.150Z",

"latitude" : 43.938,

"longitude" : -74.258,

"depth" : 12.5,

"mag" : 5.1,

"magType" : "mb",

"nst" : "",

"gap" : "",

"dmin" : "",

"rms" : "",

"net" : "us",

"id" : "usp0001yuv",

"updated" : "2015–02–11T17:15:07.000Z",

"place" : "New York",

"type" : "earthquake"

}

It looks like our MongoDB is up and running!

Step 3: Installing and Configuring Apache Drill

To install Apache Drill we’ll first grab another tarball:

wget http://getdrill.org/drill/download/apache-drill-1.1.0.tar.gz

Then, just like before, we’ll make an install folder inside our home directory, placing the contents of the decompressed .tgz file within.

$ mkdir ~/apache-drill

$ tar xzvf apache-drill-1.1.0.tar.gz

$ cp -r ~/apache-drill-1.1.0/* ~/apache-drill

And if you’d like the Drill binary directory in your system path, add this to your ~/.bashrc file:

PATH=~/apache-drill/bin:$PATH

Next we need to configure Drill so that it sees our MongoDB database. To do this first start the Drill shell by running

$ drill-embedded

(don’t be afraid if it takes a while to start). Then direct a web browser to the address http://127.0.0.1:8047. This page is called the Drill Web Console. Now select Storage from the top menu bar, and click Update next to the entry named ‘mongo’ that appears under the Disabled Storage Plugins heading. On the page that loads, click “Enable.” That’s it! Now if you type “show databases;” into the Apache Drill shell, you ought to see the database “mongo.quakedata” listed.

> show databases;

+ — — — — — — — — — — -+

| SCHEMA_NAME |

+ — — — — — — — — — — -+

| INFORMATION_SCHEMA |

| cp.default |

| dfs.default |

| dfs.root |

| dfs.tmp |

| mongo.local |

| mongo.quakedata |

| sys |

+ — — — — — — — — — — -+

8 rows selected (0.591 seconds)

And we can switch to our seismic information database by simply typing

USE mongo.quakedata;

Step 4: Manipulating a MongoDB database with ANSI SQL

A.k.a. “The fun part.” Now that we have Apache Drill installed and configured to work with our MongoDB database we can immediately start inspecting our data using a standard SQL interface. For instance if we wanted to see the different types of seismic events cataloged in our data set, we would just use the standard SQL:

> SELECT DISTINCT type FROM quakes;

+ — — — — — — — — — -+

| type |

+ — — — — — — — — — -+

| mining explosion |

| earthquake |

| quarry blast |

| explosion |

| rock burst |

+ — — — — — — — — — -+

5 rows selected (8.312 seconds)

Before we do anything more sophisticated, it would probably be good to issue this command, which tells Drill to read numeric text fields as floating point numbers:

ALTER SYSTEM SET `store.mongo.read_numbers_as_double` = true;

So what can we do with this data set? Well, let’s use this USGS page about induced earthquakes as a rough guide and look at the number of magnitude 3.0 or greater earthquakes in our data that occurred between 1980 and 2009, and between 2009 and the end of 2014. The first (1980–2009) query:

> SELECT COUNT(type) FROM quakes WHERE `time` BETWEEN '1980–01–01 00:00:00' AND '2008–12–31 23:59:59' AND mag >= 3.0 AND type LIKE 'earthquake';

+ — — — — -+

| EXPR$0 |

+ — — — — -+

| 918 |

+ — — — — -+

1 row selected (5.798 seconds)

And the second (2009–2014) query:

> SELECT COUNT(type) FROM quakes WHERE `time` BETWEEN '2009–01–01 00:00:00' AND '2014–12–31 23:59:59' AND mag >= 3.0 AND type LIKE 'earthquake';

+ — — — — -+

| EXPR$0 |

+ — — — — -+

| 1340 |

+ — — — — -+

1 row selected (3.549 seconds)

(Note that since ‘time’ is a reserved keyword, we need to enclose it in backquotes to tell Drill that we’re talking about a field in our dataset). That’s definitely more earthquakes in a much smaller time span, and our results line up approximately with what the plot on the USGS page indicates. Now let’s issue a couple new commands to inspect the average depth of the events in these sets. Do induced quakes have a lower average depth? A higher one? We can shed some light on this by making a slight modification to the last two queries. For 1980–2009 we have an average depth:

> SELECT AVG(depth) FROM quakes WHERE `time` BETWEEN '1980–01–01 00:00:00' AND '2008–12–31 23:59:59' AND mag >= 3.0 AND type LIKE 'earthquake';

+ — — — — — — — — — — +

| EXPR$0 |

+ — — — — — — — — — — +

| 8.461002178649235 |

+ — — — — — — — — — — +

1 row selected (3.018 seconds)

And 2009–2014 yields:

> SELECT AVG(depth) FROM quakes WHERE 'time' BETWEEN '2009–01–01 00:00:00' AND '2014–12–31 23:59:59' AND mag >= 3.0 AND type LIKE 'earthquake';

+ — — — — — — — — — -+

| EXPR$0 |

+ — — — — — — — — — -+

| 6.44491343283582 |

+ — — — — — — — — — -+

1 row selected (2.385 seconds)

We see now that quakes from the second set have an average depth about 2 kilometers shallower than those from the first set. This makes sense, because if a significant number of recent earthquake events are due to human activity, we would expect them to drag the all-event average closer to a depth where it’s easier for humans to reach (i.e., closer to the surface). So that’s it for this post! As you’ve seen, creating an SQL interface to MongoDB is incredibly straightforward, and I hope this guide has helped you realize what a powerful data management tool Apache Drill can be.